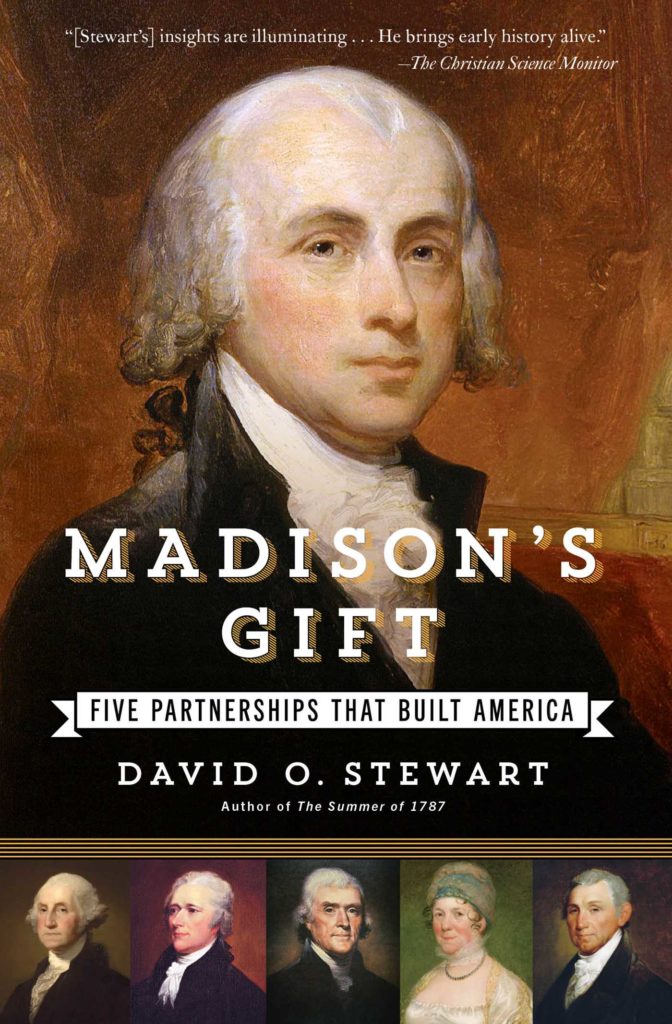

Madison’s Gift

Title: Madison's Gift: Five Partnerships That Built America

Title: Madison's Gift: Five Partnerships That Built AmericaPublished by: Simon & Schuster

Pages: 432

ISBN13: 978-1451688580

Buy the Book: Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop, Politics and Prose, Apple

Overview

#1 Amazon Bestseller!

Historian David O. Stewart restores James Madison, sometimes overshadowed by his fellow Founders, to his proper place as the most significant framer of the new nation.

Short, plain, balding, neither soldier nor orator, low on charisma and high on intelligence, Madison cared about achieving results, not taking credit. To reach his lifelong goal of a self-governing constitutional republic, he blended his talents with those of his most talented contemporaries. It was Madison who invoked the influence of his patron George Washington to lead the drive for the Constitutional Convention and an effective new government; Madison who wrote the Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton to secure the Constitution’s ratification; Madison who corrected the greatest blunder of the Constitution by drafting and securing passage of the Bill of Rights with Washington’s essential support; Madison who worked with Thomas Jefferson to found the nation’s first political party and transform the nation’s politics; Madison who drew on the martial virtues of James Monroe to guide the new nation through its first, unsteady war in 1812, and who handed the reins of government to this last of the Founders, his old friend and sometime rival. No American leader has matched Madison’s gift for joining with brilliant and diverse personalities in pursuit of great achievements.

Madison’s most important partnership was with his charismatic wife, Dolley. With unfailing charm and sure political sense, she proved an invaluable asset both to the career of her soft-spoken mate and to a nation struggling for its republican identity. Their partnership was a love story that sustained Madison through his political rise, his presidency, and his fruitful retirement.

Trailer

Praise

“[Stewart’s] insights are illuminating . . . He weaves vivid, sometimes poignant details throughout the grand sweep of historical events. He brings early history alive in a way that offers today's readers perspective.” (Christian Science Monitor)

“Stewart has a knack for offering telling details that humanize historical figures . . . Madison’s Gift is a fascinating look at how unfinished the nation was in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and how one unlikely figure managed to help guide it from a precarious confederation of reluctant states to a self-governing republic that has prospered for more than two centuries.” (Richmond Times-Dispatch)

“Stewart is an acknowledged master of narrative history. He can explain a political crisis or an ideological debate with perfect clarity and exactly the sense of urgency required to capture and hold the reader’s attention.” (The Washington Post)

“A fond portrait of the mild-mannered Virginian and implacable advocate for the young American government. . . . Historian and novelist Stewart offers a pertinent lesson on Madison's ability to forge working bonds with other founding members of the new American government, even if they did not always see eye to eye. . . . Stewart's lively character sketches employ sprightly prose and impeccable research.” (Kirkus Reviews)

Stewart examines [Madison] from a fresh angle . . . [he] illuminates much about the history-making relationships among these celebrated figures that in other books might remain obscured. Readers of history are in good hands with this dependable guide, which approaches its subject with a smooth, easy going style. (Publishers Weekly)

Videos and Podcasts

For David's talk at the National Archives, February 25, 2015, click here.

For David's conversation with Thom Hartmann of the Great Minds TV show, click here.

Watch David (and others) as commentators on Maryland Public TV's show on the crisis when the British burned Washington, DC, click here.

For a podcast of his interview on the History Author Show, click here.

Q&A

From C-SPAN's Q&A show, March 8, 2015, with Brian Lamb.

Q. The structure of Madison’s Gift is one of the most interesting parts of the book. How did you decide to build it around these five key partnerships in Madison's life?

A. I was drawn to Madison because he was such a pivotal figure in America’s early history, yet so often seems to recede from view. Many of his contemporaries were more charismatic (Washington, Jefferson) or simply noisier (Hamilton, Adams). Madison, it seemed to me, was the fellow in the back room getting the real work done, not so often the one out front getting the credit – for the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, the Federalist essays, founding the Republican Party, even the War of 1812 (for which he got lots of blame and not so much credit).

The more I read and thought about it, I realized that Madison was comfortable with not being out front and actually followed a conscious strategy of partnering with complementary personalities. As one longtime Madison friend noted, he was “ever mindful of what was due from him to others”: that’s not a dominant quality in most political leaders, who trend to the narcissism end of the personality spectrum. I decided that the whole notion of partnership was central to Madison’s personality and his career. He liked working with others and was adept at it. He was not a total “alpha male” character, which I think makes him even more interesting at a time when American leaders are having a hard time working together.

Q. Madison’s Gift traces the interesting changes in Madison's political alignment, particularly the question of the Federal government. Madison worked with Hamilton and Washington in getting the Constitution written and ratified, but later he moved away from the Federalists toward the Republican perspective, and then back again on the issue of the National Bank when he became President. What happened?

A. This is one of the three tough questions that every student of Madison has to grapple with. Some writers portray Madison as consistently following a single political philosophy through his remarkably long public career. That model, however, doesn’t fit his career very well. He was sometimes surprised by events that caused him to reconsider his previous positions, which he then modified to match real-world experience. He was, after all, a practicing politician who had to address public issues as a legislative leader, a Cabinet secretary, and then president.

On the question of the powers of the national government, Madison did not foresee that the new Constitution could be stretched to support as centralized and energetic a financial system as Hamilton created through Washington’s first administration. Madison despised that financial system, which allowed New York financiers with inside information to enrich themselves while the nation endured a number of terrifying financial panics. (Sound familiar?) Madison insisted in 1791 that the Constitution was never intended to support such a financial structure. Over the next twenty-plus years, however, Madison experienced the virtues of Hamilton’s Bank of the United States as well as tremendous frustration of trying to fight a war with inadequate revenues, a broken financial system, untrained state militias and a very small navy. Madison concluded that the bank was a good idea after all, and that a standing army and navy were essential to preserve American sovereignty. (The other two tough Madison problems? His views on state rights, and his lifelong dependence on slave labor despite his belief that slavery was immoral and potentially fatal to the American republic.)

Q. Madison’s later relationship with Jefferson seems to be key to understanding them both. What forged such a bond between these two Founders?

A. They had so much in common. They were from the same part of the world, the Virginia Piedmont country. They grew up 30 miles apart. Each was the eldest son of a very rich man and inherited great wealth, including a lot of slaves. And each was a really smart bookworm who was fascinated with government and committed to personal liberty. It would have been more remarkable if they had not become such close friends and allies.

They first met when serving in the Virginia state government in 1779 – Jefferson as governor, Madison on his executive council. Though they were friendly then, both were young enough for their eight-year age difference to hold them somewhat apart. When they were reunited in Philadelphia in 1783, shortly after Jefferson’s wife died, they met more as peers, as two single gentlemen who simply could not seem to get enough of each other’s company. Their correspondence ranged over most fields of human thought and activity, including natural sciences, government, economics, industry and agriculture. It’s somewhat reassuring that it was not always a love fest – on occasion, one might dismiss the other man’s idea a bit curtly – but it was mostly an extraordinarily intimate meeting of minds and personalities. John Quincy Adams, who worked with both and who did not pass out compliments lightly, wrote of Madison and Jefferson that “the mutual influence of these two mighty minds upon each other is a phenomenon, like the invisible and mysterious movements of the magnet in the physical world.”

Q. A fascinating thread in the book is Madison's partnership with Monroe--from Virginia friends to political rivals to Monroe's service in President Madison's cabinet. How did Madison overcome their earlier difficulties to come to rely so heavily on Monroe?

A. Madison and Monroe had two opportunities to fall out from each other. In January 1789, Monroe ran against Madison for a seat in the First Congress. Madison won the race handily and seems to have borne no ill will toward the younger man thereafter. Monroe was an affable, direct person, which surely helped smooth over the confrontation. Their later contretemps was much more rancorous. Monroe, as U.S. Minister, negotiated a treaty with the British in 1806 on maritime and trade issues. President Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison hated the treaty and immediately consigned it to the dustbin. Monroe was so deeply offended that he allowed his name to be placed in nomination against Madison in the presidential race of 1808, and the two old friends neither spoke nor exchanged correspondence for two years. The rupture healed for largely practical reasons. In 1811, Madison needed Monroe in his Cabinet as Secretary of State, Monroe longed to be in high office, and enough time had passed that Monroe was willing to ignore his injured pride. And, of course, Madison remained “ever mindful” of what was due from him to Monroe.

Q. The National Archives--through the National Historic Publications and Records Commission--has long supported the publication of the documentary editions of the papers of the Founders, including Founders Online. And you relied as well upon the Documentary History of the Ratification. How did the availability of these materials online change your research and writing process?

A. I am a huge fan of Founders Online, which fundamentally changed my research and writing in large ways and small. Most obviously, I could view most of correspondence of Madison and his contemporaries from home. Though I live in the Washington area and can get to the Library of Congress, working from home saves me two hours a day in commuting time, and I am very grateful for that saving. Also, with Founders Online I can copy-and-paste passages that I want to quote, which reduces the donkey work of transcription and also eliminates the inevitable transcription errors. Finally, Founders Online is especially valuable in the final stages of preparing the manuscript, when you look back over your research notes and realize something about the source material that your notes don’t reveal. Is that because the source document didn’t say anything about the subject, or because your notes are lousy? Every history writer keeps a list of questions or problems like that to be addressed. With Founders Online, you can double-check those problems very readily. Convenience matters.

Q. What was the biggest surprise you uncovered in your research?

A. This was my first attempt to study a female historical figure – Dolley Madison – and I enjoyed it tremendously. Some of that pleasure may be attributed to Dolley herself; she was an interesting and engaging figure. But some of my reaction was due to the different experiences of women during the early American period and their different ways of writing and talking about those experiences. I have largely studied male political figures who wrote and talked – with one eye on the historical record – mostly about public matters, rarely about their feelings. Dolley gushed about her feelings, about her beloved relatives and friends, about her annoying slaves, and about the world around her. I felt that I was looking through a new window. Sure, Dolley sometimes kept her own eye on history (notably in a letter describing how she saved the Gilbert Stuart portrait of Washington from British troops intent on burning the White House). Nevertheless, the experience made me even more frustrated by the relative paucity of historical record of women’s lives, and more sensitive to the importance of reclaiming it, even for people like me who write a lot about Dead White Men.

This exchange is reproduced by permission of Prologue Magazine, for which it was first prepared.