Fort Sumter, Where It All Began

Last weekend, on my third trip to Charleston, SC, I finally made it out to Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. Like many trips to historical sites, the visit had real power to explain events, yet the site itself was somehow smaller than its legendary role in historical memory.

The location of the site was itself entirely explanatory. Plunked down in the center of the mouth of the harbor, with spits of land a few hundred yards to either side of it, I could visualize immediately why the few Union troops under the command of Major Robert Anderson had to surrender the fort at the very beginning of the Civil War. They were sitting ducks, with no practical way to provision themselves. (This is all wonderfully recounted in Adam Goodheart’s 1861.)

The location of the fort is no accident. The land on which it rests is entirely man-made, fabricated in the 1820s and 1830s of rocks (most, ironically, hauled down by ship from New England).

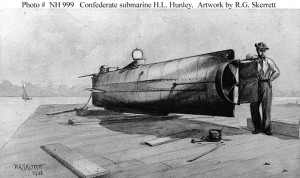

And it is surrounded by history. To the north stands the remains of Fort Moultrie, the site of Confederate artillery in 1861 but also the site of a battle with the British during the Revolutionary War. In that shipping channel to the north, the Confederate Navy launched theCSS Hunley, an underwater vehicle powered by human guinea pigs, which used a torpedo to sink the USS Housatonic. Though it was the first submarine to kill in wartime, the Hunley also killed its three crews by sinking three different times, including after the attack on the Housatonic. Like many new technologies, there were some kinks to be worked out.

The small submarine CSS Hunley was even more lethal for its own crews than for Union ships during the Civil War

To the south of Fort Sumter lies the site of Battery Wagner, where the now-legendary 54th Massachusetts Regiment, an all-black unit, mounted a bloody and unsuccessful assault on an entrenched Confederate position in July 1863. Widely celebrated as the moment when African-American troops first demonstrated their courage and bravery under withering fire, the story is retold well in the movie Glory, starring Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman.

Standing on the rebuilt walls of Fort Sumter, which were largely reduced to rubble during months of Union Army bombardment during the Civil War, it seemed like there was too much history from too many different episodes crammed into that narrow space.

But that is a pattern in human history. John Keegan’s Face of Battle recounts the pivotal battles of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme, fought across five centuries apart and all in the same neighborhood of Belgium. Crossroads of trade and human traffic have always been where our murderous proclivities flare into epic combat.