Killing Them Softly

Death plays a big role in most history books, and definitely in biographies. The death of a central feature often concludes a book. Even if the book’s story ends before the main characters shuffle off this mortal coil, readers want to know how it all ended for the people they have spent several hours reading about, which usually leads to an epilogue.

This question is on my mind because I’ve just written of the death of James Madison, for my current nonfiction project (aiming at publication in the second half of 2014, if all goes well). I find that writing about a character’s death is important to my views about a figure. Death is a great leveler. We arrive in life naked and leave it the same. How people meet their deaths, and the reactions of those close to them, is significant.

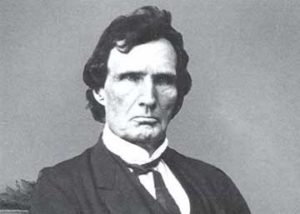

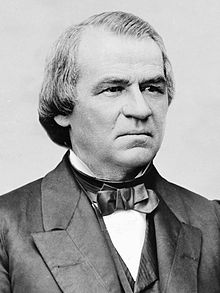

I first confronted these issues in my second book, Impeached, about the Andrew Johnson impeachment trial in 1868. I had to examine the deaths of the two great protagonists of the impeachment struggle: Rep. Thaddeus Stevens and President Johnson.

Just weeks after the conclusion of the impeachment trial, Stevens passed from this world with characteristic flourishes. He wisecracked — when a visitor told him he looked well, Stevens replied, “It’s not my appearance that troubles me. It’s my disappearance.” His longtime African-American housekeeper and presumed lover, Lydia Smith, sat vigil at the foot of his bed, ever faithful. And he left instructions that he be buried in a cemetery in Pennsylvania that accepted whites and blacks alike, making his death a teaching moment for the nation. Virtually the entire town of Lancaster lined the streets for his funeral procession. I admired Stevens all the more.

Johnson’s death in 1875 offered characteristic flourishes, too, but also softened my generally unfavorable view of him. He died shortly after winning a seat in the U.S. Senate from Tennessee, climaxing a five-year battle to return to public office; Johnson never stopped being a tough hombre. He directed that he be buried with his head on the copy of the Constitution he carried with him through life, and wrapped in the American flag. There’s a bit of grandiosity there, but strength of character, too. And his daughter faithfully attended him through his final days after a stroke laid him low.

For my next book, American Emperor, I could find little about the final days of Aaron Burr. Since the book was published, a wonderful account of the final summer of his life in 1836, from a contemporary diary, has been published by Martha Smith Kakuk and Ray Swick of Blennerhassett Island State Park. I wish I had been able to use it. It shows the loneliness of Burr’s last months, with only a cousin and a paid attendant to look after him through powerful mood swings and the frustrations of declining health and strength. It is a poignant picture of Burr, something of a corrective to his generally negative reputation, yet shows also the isolation that he created for himself.

James Madison’s demise in 1836 was, appropriately enough, best chronicled by his slave valet, Paul Jennings. For a man who lived in the midst of slavery all his life, who thought it an abomination, who worried that slavery would destroy the nation, and who never figured out a way out of slaveholding for the nation or for himself — of course, a slave would be the one to record his final moments. The only other person present was a cherished niece. It was a quiet end, one that fit a quiet man who moved the world.

James Madison’s demise in 1836 was, appropriately enough, best chronicled by his slave valet, Paul Jennings. For a man who lived in the midst of slavery all his life, who thought it an abomination, who worried that slavery would destroy the nation, and who never figured out a way out of slaveholding for the nation or for himself — of course, a slave would be the one to record his final moments. The only other person present was a cherished niece. It was a quiet end, one that fit a quiet man who moved the world.