WWI: Who was the enemy?

As the World War I centennial continues to gear up, and as I slouch to the end of my novel on the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, I have stumbled upon the most remarkable French memoir of the war — Poilu. (Thanks to Andy Dayton for recommending it.)

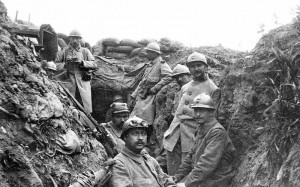

Louis Barthas was a barrelmaker in the Languedoc region of Southern France in the summer of 1914, when he was called into the army. A 35-year-old father of two small boys, Barthas was a committed socialist who plainly had a solid education. For the next 54 months — that’s four and one-half years — Barthas served in the French infantry. Remarkably, he endured some of the bloodiest battles of the Western Front, including Verdun. Through that whole time, he kept a journal of his experiences. His fellow soldiers knew about his journal and urged him to tell the real story of life in the trenches for the French poilus (“the hairy ones,” because they grew whiskers).

Barthas’ journal was first published in France in 1978, and only this year has been translated into English. Like any journal, it has a good bit of repetition. Also, every day was not as interesting as every other day. But the overall impact of the book was, for me, profound. Barthas — who never rose above corporal and never aspired to rise as far as corporal — makes it clear that his principal enemies for four and one-half years were French commanders, not German soldiers.

Along the way, Barthas relates some of the things we know intellectually about trench warfare, but which he makes vivid and unavoidable.

- Building a good trench is important, and a tremendous amount of work. Every rainfall prompts hours of effort to repair damage to the trench. He describes a trench at the beginning of the war, “before the Germans showed us just how to make them”: “A wide, shallow stream at the bottom. No protective barbed wire. No parapets, no loopholes [to shoot through]. No firing step. No trace of a shelter for us.”

- The living conditions were unimaginable, requiring the soldiers to get used to “the cannon’s roar, the musty smell of rotten flesh, the fat venomous flies, the ticks, the worms, the rats, everything unclean and impure that swarms and flourishes in a charnel house.”

- Some scenes were so vile that they would make Hieronymous Bosch shrink away in shame. In an attack on a German trench, Barthas found “An unfortunate fellow was stretched out, decapitated by a shell. . . Beside him, another was frightfully mutilated. . . [a few steps beyond] I see, as if hallucinating, a pile of corpses, almost all of them Germans, that they had started to bury right in the trench. . . . ‘There’s no one here but the dead!’ I exclaimed. . . I finally found some living souls, with haggard eyes, leaning on each other in threes and fours like frightened beasts, not even looking around.”

- Burying his own dead: “We only had six corpses to get rid of, and they were very close to the trench. . . . You pushed the cadaver into a shell hole, tossed a few shovelfuls of earth on top, and on to the next one.” Barthas had to collect the identity tag from each corpse, rifling pockets and slicing chains. “It seemed like a profanation to us, and we spoke in whispers as if we were afraid of waking them up.”

Barthas offers powerful observations on the nature of the war he fought for so long.

- “In a war like this one, combat meant mostly being a target for [artillery] shells. The best leader wasn’t the cleverest tactician, but rather the one who knew best how to keep his men alive.”

- “We were hardened against any emotion. We cared only about our own fates. War is the best teacher of egoism.”

Barthas was uniformly contemptuous of his own officers — the colonels, captains, and lieutenants (save for one) who lurked back in well-built dugouts and tents, “holed up in a bunker, ear stuck to a telephone.” One captain led his unit in every direction but the correct one, prompting Barthas to observe, “the poor guy read his map like a carp reading a prayer book.” The poilus, he insisted over and over again, did not fight “because of patriotism, or to defend the rights of peoples to live their own lives, or to end all wars, or other nonsense. It was simply by force, because, as victims of an implacable fate we had to undergo our destiny. . . . At the slightest hint of revolt we would be ground to bits.”

But at times the soldiers did revolt, on both sides of the trench line. He recounts an episode in the fall of 1915 when his unit, drenched by a cold rain, was poised to press an attack. The order came to move forward. “The men started to protest violently at word of this order. They didn’t have any spirit of adventure. They weren’t curious at all. The sergeant was perplexed. I suggested that he respond this way: ‘The men ask that the section chief lead them at the head of the column.'” After considerable passing of messages between those poised to attack and their commanders in the rear, the attack was called off.

When the French military police (the “gendarmes”) cracked down too hard on soldiers for slipping away from their posts to buy food from nearby villages, the soldiers did not hesitate to respond. “One day they found two gendarmes swinging from the branches of a pine tree, with their tongues hanging out. From that moment, the poilus could go get food in the neighborhood without worrying about a thing.”

The common soldiers on both sides accommodated each other on a number of occasions recorded by Barthas. In December 1915, when the rain was so heavy that trenches overflowed, both Germans and Frenchmen had to climb out or drown. “We therefore had the singular spectacle of two enemy armies facing each other without firing a shot.” Both sides were careful not to shoot at the other’s kitchens and food personnel, recognizing their common interest in letting “the peaceful cooks go about their business in peace at their kettles.”

On another occasion, a German soldier blundered into Barthas’ trench and a French soldier prepared to throw a grenade at the intruder. “I held his arm. I will always be faithful to my principles as a socialist, a humanitarian, even a true Christian, even if they cost me my life, of not firing on someone unless in legitimate self-defense. And was it in our interest to break the neighborly relations which existed between our two adjoining outposts?” The German turned and ran.

In the summer of 1916, Barthas’ unit was again posted very close to German trenches. Too close to fight, as it turned out: six meters away. In the area, “calm and tranquility” reigned. Soldiers “smoked, others read, some wrote, a few squabbled.” Indeed, “the French and German sentries [were] seated tranquilly on their parapets, smoking pipes and exchanging bits of conversation from time to time, like good neighbors.” When the French learned that their officers were going to order them to open fire on their “good neighbors,” the poilus warned the Germans to take cover.

Sent out on patrol against German lines, the poilus became adept at fabricating tales for their officers. On one occasion, a patrol reported that a new poison gas was devastating the German lines, even though they poilus had never reached the German trenches. “That made our big bosses happy,. . . as well as the scouts, who all came back at such little risk.”

In 1917, when their commanders demanded that the French patrols bring back German prisoners for questioning, the poilus were equal to the challenge. Returning empty-handed, “everyone swore that the Boches [Germans] simply wouldn’t surrender, and they were forced to kill every last one of them.”

In the early summer of 1917, news of the Russian Revolution against the tsar caused “a wind of revolt [to] blow across almost all the regiments.” Barthas’ regiment elected a “soviet” of three men from each company to take command. Barthas was selected, but refused the honor. “I had no desire to shake hands with a firing squad, just for the child’s play of pretending we were the Russians.”

Barthas helps explode the myth of the implacable German soldier who always fights to the death. In late summer of 1916, his unit captured an entire German unit which, after deciding it was “useless to defend themselves, unanimously raised their arms, crying ‘Comrades! Comrades!” After gathering up the prisoners, the poilus found the body of a German officer, “his head bashed in, and beside him a shovel covered with blood. It seemed clear that, when he didn’t want to surrender, his men had gotten rid of him.”

Barthas’ own survival was very close to a miracle. He recounts a dozen occasions on which his sense of danger caused him to shift position, thereby saving his life and often those of his fellows. He lived long enough to see the next war in France, during which his son served in the French Resistance, and died in 1952. In all of his journals, though, Louis Barthas never describes an occasion when he killed an enemy soldier.

Very interesting. My father, who served in Okinawa, also recounted instances of Kamikaze pilots surrendering rather than going through with their suicide missions. And my grandfather, who helped in the Y. M. C. A. in France and Germany because he was too old to serve in the army in WWI, often felt that his biggest enemy was his superior.

Our family are big fans of IMPEACHED, by the way. My son wants to be a history major.