Babe Ruth: Know your enemy!

Babe Ruth was a great pitcher before he was a great hitter. Doesn’t it seem likely that one of the reasons he was a great hitter was because he had been a great pitcher?

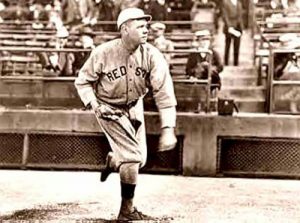

Playing for the Boston Red Sox from 1915 to 1918, the Babe was probably the best left-handed pitcher in the American League. He won 78 games and lost only 40, racking up an E.R.A. of 2.28 for his entire pitching career. He was fabulous in clutch situations, setting a record that stood for decades by pitching 29 consecutive scoreless innings in World Series games.

By the 1919 season, though, the Babe was getting restless. He wanted to play every day. He thought he could make more of a contribution as a hitter and outfielder, and have more fun, too.

In the 1919 season, he split his time between pitching and the outfield, setting a new home run record with 29 shots out of the park, but also going 9-5 as a pitcher. That was enough to persuade the Babe. He wanted to play outfield full time and if that meant leaving Boston, then so be it. He campaigned to be traded, and the Red Sox accommodated him by selling his contract to the New York Yankees.

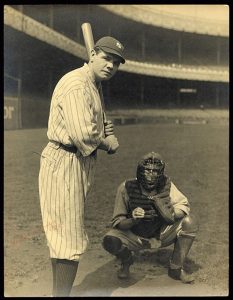

The rest is the stuff of legend. Blasting 54 homers in his first season with the Yanks and 59 in his second, Ruth transformed baseball. He inserted the power game into what had been predominantly a scrappy, singles-and-stolen-bases game.

Babe Ruth in 1920, his first full season with the New York Yankees, when he hit 54 home runs.

But he also hit for high averages, finally retiring with a lifetime batting average of .342. He was an amazing hitter.

But I wonder if he didn’t have a terrific advantage as a hitter because he had been a star pitcher? A huge part of hitting is guessing what the pitcher is going to throw (fast ball? curve? slider?) and where he’s going to throw it (inside/outside? high/low?). As said by the man who broke the Babe’s career home run record, Henry Aaron, “Guessing what the pitcher is going to throw is eighty percent of being a successful hitter. The other twenty percent is just execution.”

It stands to reason that someone who has been a pitcher at an elite level, as Babe Ruth was, will have special insight into a pitcher’s strategies. A hitter with that experience — a hitter like Ruth — has walked in the other guy’s moccasins. He should be able to read signs of fatigue, mental and physical. He should be able to suss out the individual pitcher’s reliance on certain pitches and pitch locations in critical moments.

It’s as though one of our generals in Afghanistan had spent five years fighting as part of a Taliban cell. Wouldn’t that provide a remarkable advantage in figuring out the other enemy’s tendencies and preferences?

I’ve read widely about Ruth without ever seeing a claim by the Babe that he consciously used his experience as a pitcher while he was up at bat. Nor have I seen any baseball analyst emphasize that experience in explaining Ruth’s extraordinary career as a hitter. But it makes sense to me.