Washington Navy Yard: Some Tough History

For someone writing a book about James Madison (that’s me), yesterday’s mass shooting at the Washington Navy Yard has powerful echoes. While the new national capital was being hacked out of forest and swamp in the 1790s, Congress arranged to buy land for a naval support facility. Soon the navy yard at Washington City was the center of America’s small but tough fleet of armed frigates and smaller warships.

(For a great history of the early Navy, check out Ian Toll’s Six Frigates.)

Perhaps the enduring image of the Navy Yard has been when Navy Secretary William Jones personally supervised its destruction in late August 1814, in order to keep its valuable stores and munitions from falling into the hands of the invading British Army. British troops burned down the Capitol and the Executive Mansion, but the American forces blew up the Navy Yard. Not a glorious day for American arms.

Through Madison’s second administration, Navy Secretary Jones was an oasis of competence in a desert of Cabinet ineptitude. Madison later called Jones the best Navy Secretary the nation had known. Since there had only been a handful at the time, one of whom was a known alcoholic, the praise rang more hollow than it should have. While the army stumbled and bumbled its way through much of the War of 1812, the Navy won victories on the Atlantic and the Great Lakes that buoyed the nation’s morale in very dark days.

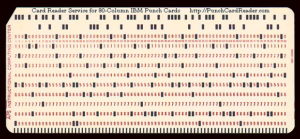

Like many folks in the DC area, I have my own connection to the Navy Yard. For a month in the summer of 1971, I worked there at a Veterans’ Administration office. My job, with about a dozen other white college students, was to file IBM punch cards in alphabetical order in about 50 massive file cabinets; because the cards were not in alphabetical order, we crisscrossed the flourescent-lit storage space, dragging out file drawers and flipping through them to find the exact correct space to file “Stewart, Daniel H.” between “Stewart, Daniel G.” and “Stewart, Daniel I.” Mind-numbing, in the extreme.

Managers instructed us to file 800 cards a day. Working feverishly, I barely could file 400. Towards the end of my first week, a longtime employee gave me a sidelong glance as she listlessly pawed through a file cabinet.

“Honey,” she said, “you working way too hard.”

“But they said we had to file 800 a day,” I protested.

“Two hundred is plenty.” She slammed her drawer shut for emphasis.

I looked around the room. It had all the energy of a vacant lot. The year-round employees sashayed around, chatted, left for the rest room for remarkably long breaks. For the next three weeks, I brought a book to work with me. Every hour, I took a 15-minute break in the men’s room to read with the other shirkers. I read The Brothers Karamazov in that rest room.

After a month on the job, I quit to volunteer at Sen. George McGovern’s office. I just walked in and they put me to work. McGovern was preparing to run for president in 1972 as the antiwar candidate. I wanted to end the Vietnam War, and McGovern seemed the best way to make that happen. After two months working for him, I had developed a different form of disillusion — a story for another day –and decided to go back to college.

But my month at the Navy Yard has always stuck with me. All that empty work and those people who hated their jobs. And now this terrible shooting. So sad.