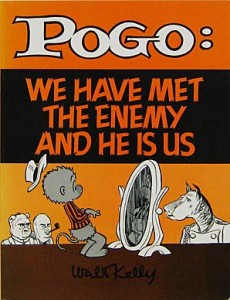

We have met the enemy and he is us

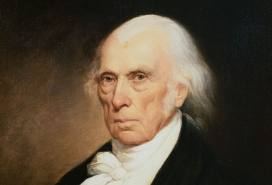

James Madison and Walt Kelly, creator of the Pogo comic strip, had this much in common: they both concluded that we are the problem.

Kelly issued his most famous pronouncement — “We have met the enemy and he is us” — on a poster for the first Earth Day in 1970.  For those of us sweltering through the heat and storms of summer 2012, the environmental conclusion that we are the problem becomes ever more difficult to deny.

For those of us sweltering through the heat and storms of summer 2012, the environmental conclusion that we are the problem becomes ever more difficult to deny.

The broader application of Pogo’s Truth was plain in 1970. Its application to the Vietnam War was terribly uncomfortable: our foggy goals, the massive bloodletting, the poisoning of the land we said we wanted to save.

So . . . Madison figures in here? Yes, ma’am. I’ve spent today reading the debates of the First Congress. Green with envy, aren’t you? Well, it’s pretty good stuff, especially when Madison gets on his feet. His big day was June 8, 1789, when he introduced a package of amendments to the Constitution.

Now, Madison wasn’t a big fan of amending the Constitution. He thought the charter of government was the best we were going to get and that monkeying around with it was a dangerous thing to do. But he listened to his adversaries during the ratification process and concluded that some of their ideas for amendments were not so bad. If amendments did no harm and made his opponents feel better about the Constitution, he promised to support them.

But he was a remarkably diffident advocate. Introducing his proposal for a Bill of Rights, he said he “never considered this provision so essential,” but concluded that it “was neither improper nor altogether useless.”

Whoa: not “altogether useless”!

If bills of rights were established in the states as well, he concluded, “although some of them are rather unimportant, yet, upon the whole, they will have a salutary quality.”

Why? According to many fervent and self-appointed defenders of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights stands as our bastion against the hideous over-reaching government. Madison, didn’t think so. “The great danger,” he told his colleagues in June 1789, “lies rather in the abuse of the community than in the legislative body.” He thought a Bill of Rights might do some good as “one means to control the majority from those acts to which they might otherwise be inclined.”

Us. We’re the problem.