Five Books on Impeachment

The conservative-inspired “Impeach Obama” campaign will wax and wane over the next two political years, a weird residue of the benighted effort to impeach President Bill Clinton fifteen years ago. Even though the Impeach Clinton effort failed somewhat ignominiously, it has empowered true believers of the Left and Right to think of impeachment as an ordinary tool of American politics.

Thus, as the administration of President George W. Bush limped through its final days, liberal Democrats in Congress introduced resolutions to investigate his impeachment, or to flat-out impeach him. By 2008, liberal gadfly Dennis Kucinich of Ohio worked to force a vote in the House of Representatives on his claims that Bush’s foreign invasions based on false efforts (“he lied us into war” in Iraq) warranted his removal from office.

Now it’s President Obama’s turn. Impeachment advocates, including Sarah Palin, recite a laundry list of executive actions by Obama that supposedly exceeded his constitutional powers and justify impeachment and removal from office: actions on immigration policy, lies about Obamacare health insurance coverage (“if you like your coverage, you can keep it”), and launching the United States into “war” in Libya.

That these efforts have been doomed is a blessing for our constitutional government, yet they all reflect a fundamental confusion about what impeachment involves. That confusion has persisted in American government since the Constitution was ratified in 1788. The core of the problem is the constitutional standard for impeachable offenses — that the accused federal office-holder have committed “treason, bribery, or high crimes and misdemeanors.” “Treason” and “bribery” are never the issue. But what the heck are “high crimes and misdemeanors”? [Answer at the end of this post.]

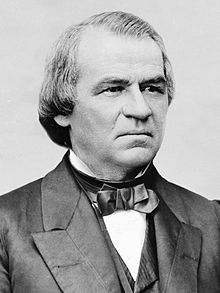

My engagement with impeachment has been long and fairly intense. I defended a federal judge from Mississippi in a Senate impeachment trial and then filed a lawsuit challenging the Senate’s trial procedures in Nixon v. United States, a case that I ultimately argued (and lost) before the U.S. Supreme Court. And I wrote a book, Impeached, about the 1868 impeachment trial of President Andrew Johnson, in which Johnson won acquittal by a single vote in the Senate.

For those seriously interested in the question of impeachment beyond the demagoguery of the moment, I recommend the following five books:

- Impeached, by moi — What did you expect me to recommend? The Johnson impeachment was a confusing mess. The accusations against him seemed picayune, yet the passions of the impeachers were titanic: they believed the fate of the Union and the outcome of the Civil War turned on Johnson’s trial. Dark men prowled Washington’s streets with satchels of money, looking for Senators to bribe on the impeachment vote. Somehow, the opaque impeachment clause of the Constitution brought about a peaceful resolution of a bitter national crisis.

- Impeachment: A Handbook, by Charles L. Black, Jr. — Not so much a book as a quiet conversation with a thoughtful constitutional law professor at Yale. Black lucidly explains each of the elements of the impeachment process and what they aim to achieve. I don’t agree with all of his conclusions, but it’s a valuable book.

- Impeachment: The Constitutional Problems, by Raoul Berger — In many ways, this volume is the polar opposite to Black’s. Berger disagrees with Black on several points and occasionally loses his way in hoary English impeachment precedents from medieval days. Meaning no disrespect to Berger, I find his book most valuable for proving that historical analysis of English impeachment will never solve the fundamental problems of making sense of impeachment under the U.S. Constitution. You may conclude otherwise.

- The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson, by Michael Les Benedict — A notable work because Benedict was willing to say out loud that President Johnson should have been impeached. He spends a good deal of time analyzing congressional voting patterns in the 1860s, but you can skip those sections.

- The Breach: Inside the Impeachment and Trial of William Jefferson Clinton, by Peter Baker — Despite the occasional journalistic hyperventilation, this examination of the Clinton impeachment train wreck provides an agonizing dissection of how the nation careened into its continuing infatuation with presidential impeachment.

OK, now my thoughts on “high crimes and misdemeanors”: they must be an abuse of the president’s constitutional powers that justify his removal from office, though they need not be a crime. Lots of crimes are penny-ante. Take the Clinton case. President Clinton lied under oath about his sex life. I abhor his lie. It was not, however, an abuse of his official powers.

Is that subjective? You bet. Although impeachment is dressed up in judicial processes, it is a profoundly political act: Congress removes the elected leader of the nation, the only public official elected by the entire nation. You don’t impeach and remove a president because you don’t like his policies. So long as he can reasonably claim that he acted within his powers — even if a reasonable case can be made that he didn’t — then he should not be impeached.