Winning by Losing: Babe Ruth at the 1921 World Series

When Babe Ruth led the New York Yankees into their first World Series ever in 1921 — 95 years ago — he had just finished what may have been the best season a hitter has ever had: 59 home runs, 161 RBIs, a .378 batting average. He scored 177 runs. Opposing teams hated to pitch to him; he impatiently endured 145 bases on balls.

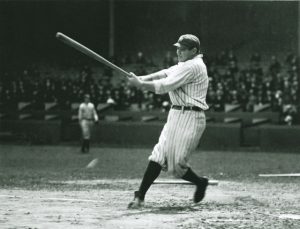

Babe Ruth taking a mighty swing in 1921 season — look at the size of that bat!

Baseball fans eagerly anticipated the Yankees’ October showdown with their crosstown rivals, the New York Giants. Though Babe had played in three World Series for the Boston Red Sox, he had been a star pitcher then. Now he had made himself the most feared hitter in the sport. What havoc might this awesome “Sultan of Slug” wreak on the poor Giants?

The reality was both much less than fans had hoped, and much, much more.

Take what they give you

That’s the truism that hitters have to learn, and the 26-year-old Babe knew it well. In the early games of the Series, the Giants’ pitchers wanted no part of him. They walked him four times in the first two games. And the Babe was eager to do something great. He struck out twice. Still, he drove in a run with a single in the first game and scored a run in the second, stealing two bases in the process. Fabled sportswriter Heywood Broun drew an indelible portrait of the rampaging Ruth on the basebaths:

“It is startling to see so huge a man suddenly abandon his fixed post at top speed. If some morning the Woolworth building should lean over and pat a passer-by on the back without preliminary warning, somewhat the same effect might be created as that which attends the sight of Ruth’s entire body in motion all at once.”

The Yanks took the first two games by 3-0 scores, jumping into the lead in the best-of-nine series (1921 was the last time baseball used the best-of-nine format).

Ruth drove in two more runs in Game 3 with another single and was walked again, but the Giants roared back to take the game in a laugher, 13-5. When Ruth was pulled for a pinch runner in the eighth inning, some fans booed. They didn’t know the truth. Babe’s aggressive baserunning had brought on a painful injury.

As big as an elephant’s thigh

Sliding into third base in Game 2, Babe had torn up an elbow on the pebbly, uneven basepath. He aggravated the injury performing the exact same act in Game 3. When the Yanks announced that he wouldn’t play in Game 4, panic struck among their fans.

“The Yankees have lost not only his great hitting,” the New York Times wrote, “but also the smartness and cunning that this ball player brings to a team.” The article pointed out that Ruth “conceived and directed most of the daring base running to the credit of the Yankees, and his value as a strategist has excelled even his ability to punch the ball to distant regions.”

Not just a power hitter, eh?

Babe Ruth led the New York Yankees into the 1921 Series against the New York Giants of John McGraw and Frankie Frisch.

But in Game 4, Babe confounded the experts and the doctors. Playing despite his injury, he smacked a home run and single in a losing cause. Now the series was even.

Game 5 was the watershed. Despite the elbow injury and a knee that was going lame, Babe took his post in left field and his third spot in the batting order. His elbow was on fire. The knee was shaky. He wasn’t the real Babe Ruth. He struck out three times, yet led his team to a win with a startling bunt single in the fourth inning and coming around to score winning run by the end of the inning. “Babe Ruth knocks the Giants over with a feather,” Heywood Broun announced, vividly describing the big man’s bunt:

“Babe’s bat was vibrating up behind his shoulder and he was staring intently at the wooden bleachers in right [field]. It was a gorgeous piece of character acting for as the ball came up to the plate, Babe suddenly checked his swing and thrust his bat straight out across the plate. The ball dropped five feet away from the plate, lazily rolled over twice and stopped. And like a bigger ball with a bad dent in it, Ruth rolled toward first, going lickety split and limpety-limpety.”

To equal the distance of Babe’s longest home run, Broun added, Babe would have to hit that bunt 105 and one-half times, but “that little tap served just as well.”

It was the Babe’s final highlight in the Series. The Yankees, alarmed by the spreading infection in his arm and by his gimpy knee, disqualified him from further play. Yankee Manager Miller Huggins said after Game 5, “How he had been able to do what he had done during the afternoon made me look at him in amazement. It was an exhibition of gameness that will go down through baseball history.” Another great sportswriter, Grantland Rice, wrote that Babe’s arm was so swollen that it “looked like an elephant’s thigh.”

With Ruth sidelined, the Giants took the series, five games to three. Babe took the field one more time, pinch hitting in the final inning of the final game. He grounded out weakly.

Though the series had been grueling and disappointing, the Babe had only burnished his emerging legend. “Ruth had the greatest individual following in baseball before the series opened,” the New York Times wrote, “and he has passed out of the series a bigger figure in baseball than he was at the start.”