225th Birthday of America's Bill of Rights!

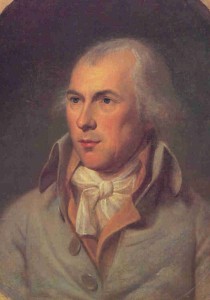

The semi-dashing James Madison in 1794, five years after drafting America’s Bill of Rights.

I’m delighted to be among the first to proclaim the 225th anniversary of the ratification of America’s Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments to the Constitution. Those amendments protect individual liberties that Americans hold most dear, and became central to our national character after the Fourteenth Amendment (adopted in 1868) applied them against state governments as well as the federal government.

I thought about writing a book about the enactment of the Bill of Rights as a natural sequel to my first book, The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution. Ultimately, though, I concluded that the story lacked the drama and oomph I was looking for. In truth, America backed into the Bill of Rights, which was adopted without much enthusiasm. I did get to write about the episode in Madison’s Gift, but as part of the much larger story of James Madison’s remarkable contributions to the nation.

The surprising truth is that the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention of 1787 didn’t spend much time thinking about protecting individual liberties. Their concern was with creating an effective new government.

In the last week of the convention, George Mason of Virginia and Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts proposed a Bill of Rights; several state constitutions had one. The other delegates, however, swiftly defeated the effort. They offered the counter-arguments that it wasn’t necessary (how could the federal government threaten personal rights?) and that it would be dangerous to list some protected rights because they might inadvertently omit others that should have been listed. Mostly, though, they thought Mason and Gerry were trying to sidetrack completion of the Constitution, which both men soon refused to sign.

Once the Constitution was released to the public, the most effective criticism of it turned out to be the absence of a Bill of Rights. The pro-Constitution forces, led by Madison and Alexander Hamilton, won ratification by the states over the opposition, but Madison became persuaded that a Bill of Rights was necessary to quiet public doubts about the new government. Indeed, he made it a central campaign promise when he ran for Congress in early 1789 against James Monroe.

Accordingly, Madison arrived in Congress in New York City on a mission to win approval of a Bill of Rights. Though many congressmen and senators thought a Bill of Rights wasn’t very important and resented spending time on it, Madison insisted, arguing that it would not be “altogether useless” — a surprisingly modest claim.

Federal Hall in New York City, where Madison proposed the Bill of Rights and Congress approved them in 1789.

Madison proposed a long list of rights to be protected. His list was consolidated by the House, then pared down much further during the then-secret deliberations of the Senate. Consequently, we have no good explanation for many of the wording choices in the final text of the amendments. That has helped fuel considerable litigation — as with, for example, the clumsily worded Second Amendment and its right to bear arms.

One of the dropped Madison amendments would have ensured freedom of speech and religion against state intrusions, a protection that would have to wait for the Civil War and the Fourteenth Amendment.

The final ratification came more than two years after Congress adopted the amendments, on December 15, 1791, from — fittingly enough — the state of Virginia.

Congress had sent twelve amendments to the states in 1789, but only ten were ratified then and became known as the Bill of Rights. Of the two that were not adopted in 1791, one was adopted two centuries later as the Twenty-Seventh Amendment, and decrees that congressional pay raises cannot take effect until after a new Congress is elected. The twelfth proposed to limit the size of congressional districts to 30,000 citizens; it was not adopted and swiftly became moot as the nation grew.

Madison’s prediction about the importance of the Bill of Rights proved prescient. He acknowledged that in times of crisis — war and civil strife — governments will violate individual rights and no “parchment barriers” are likely to stop them. But by enshrining personal rights in the Constitution, he argued, those rights would become entrenched in the national character and ultimately would be cherished and protected in many situations.

Happy Birthday!

I have just finished your excellent book “The Summer of 1787” and have reviewed it on Amazon (https://www.amazon.com/review/RTHREOTNT8NTP/ref=pe_1098610_137716200_cm_rv_eml_rv0_rv) and Goodreads (https://www.goodreads.com/review/show/1665835546).