Trump: Haunted Anew by the Ghost of Andrew Johnson

More echoes of the benighted Andrew Johnson Administration of 1865-69 reverberate around President Trump with the current logjam at the top of the Consumer Financial Protection Board. Deputy Director Leandra English asserts the statutory right to direct the agency following the resignation of its director; claiming to act under a different law, President Trump has named Mick Mulvaney to serve as acting director.

The power of the past (Andrew Johnson) to haunt the present!

All of which hearkens back to the those halcyon days in early 1868 when the nation had two Secretaries of War. Edwin Stanton was appointed by Abraham Lincoln, confirmed by the Senate, and retained in office by President Johnson for almost three years. Unhappy with Stanton’s commitment to enforcing Reconstruction laws that aimed to assist the freed slaves, Johnson tried to fire Stanton in late 1867. Under the Tenure of Office Act, the Senate refused to confirm the dismissal, so Stanton remained in office.

In February 1868, Johnson tried again, this time ignoring the Senate and simply sending an interim appointee — the entirely forgettable General Lorenzo Thomas — to take over the War Department.

Sleeping on the Job

Stanton, however, refused to relinquish the office, or even leave the building. He slept in the office and ate his meals at his desk for nearly three months while his congressional allies impeached Johnson and placed him on trial in the Senate. The principal charge against Johnson was that his appointment of Lorenzo Thomas violated the Tenure of Office Act. That law (not accidentally) provided that any violation was a “high crime and misdemeanor,” copying the language of the Constitution’s impeachment clause

The legal situations are not entirely parallel. The English/Mulvaney showdown involves dueling claims under the CFPB’s authorizing statute (which provides that the deputy director serves as acting director when the top position is vacant), and the Federal Vacancies Reform Act (which gives the president authority to appoint fill vacant agency positions on an interim basis, pending Senate confirmation of a successor). Neither law states that violations are high crimes and misdemeanors. And the Tenure of Office Act was mostly repealed, then its remnants were invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1926 as unconstitutional (Myers v. United States).

There’s a stark political distinction between the situations, as well. Andrew Johnson faced a Congress dominated by political foes who desperately wished for his removal from office and the public scene. In contrast, today’s Republican-majority Congress has shown a steady devotion to the president.

Yet the factual similarity is weirdly evocative, a symptom of a polarizing chief executive and bitterly partisan times. Also, it arises just two months short of the 150th anniversary of the Thomas-Stanton showdown in the War Department’s offices, which I wrote about in Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy. That confrontation remains one of my favorite moments in American history — a moment more reminiscent of Monty Python than of the Federalist Papers. As recorded by a witness who transcribed the exchange, Thomas spoke first:

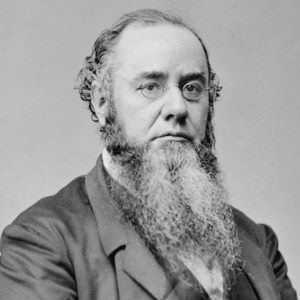

Incumbent Secetary of War Edwin Stanton

THOMAS: I am Secretary of war ad interim, and am ordered by the President of the United States to take charge of the office.

STANTON: I order you to repair to your rooms and exercise your functions as Adjutant General of the Army.

THOMAS: I am Secretary of War ad interim, and I shall not obey your orders; but I shall obey the orders of the President, who has ordered me to take charge of the War Office.

STANTON: As Secretary of War, I order you to repair to your place as Adjutant General.

THOMAS: I shall not do so.

STANTON: Then you may stand there if you please, but you cannot act as Secretary of War; if you do, you do so at your peril.

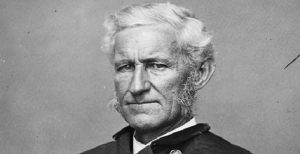

Wannabe Secretary of War Lorenzo Thomasril.

THOMAS: I shall act as Secretary of War.

Shortly after that ludicrous exchange, Thomas left. He attended Cabinet meetings for several weeks until Johnson faced reality. He appointed a permanent replacement for Stanton, General John Schofield, who proved acceptable to much of Congress. Thomas never got into the War Department office.

Oh, and Johnson was acquitted in his impeachment trial by a one-vote margin. Kansas Senator Edmund Ross cast the deciding ballot for acquittal. In my book, I concluded that Ross’ vote was purchased with cash or patronage promises or both, which is another story. . . .

For this week’s face-off at the CFPB, I certainly hope someone records any confrontation between English and Mulvaney. I can’t help but wonder if one of them will end up spending a few weeks barricaded in the building until the courts resolve the matter.

Which leads to the inevitable questions: Does English or Mulvaney have the key to the office? And which will arrive first in the morning?

Sec’y of War was a strange title. Robert Gates is now Secretary of Defense which sounds better.